Coastal erosion on Mersea

Mersea Island Courier 23 February 2024

Coastal erosion and sea level rise on Mersea

In a recent Courier we looked at how sea level rise is likely to affect Mersea and nearby mainland villages, with the next 25 years likely to see something similar to the 28-30cm rise we have seen over the last 100 years. One of the major consequences of that is a significant increase in the rate of coastal erosion.

The changing shape of Mersea Island

For centuries land has been lost to the sea either through sea level rise or erosion – and often a combination of the two. For example, if we go back to Anglo-Saxon times when the Lindisfarne monk Cedd established St Peter’s church in Bradwell, it is quite possible that the Blackwater estuary was confined to the deep channel that is only about a third of the width of the modern estuary. Subsequent sea level rise has created the ‘flooded estuary’ that we see today.

As such the shape and size of Mersea Island’s landmass has changed dramatically over the years. However, not all of that has been directly due to sea level rise. Even in the last 100 years there have been very significant changes in the size and shape of the island due to erosion – as well as to a certain extent the deposition of eroded material on other parts of the island.

The grey ‘mud’ that you can see when the tide goes out was originally land – and much of it until relatively recently. For example, the Cocum Hills, which are now about a mile off Cudmore were until WW2 actual hills of mud, and in the 1920s and 30s cattle grazed in the ‘Cattle Gut’ – now offshore from Cudmore. While a century ago Cobmarsh island was around twice its present size. If you want to know more – have a look at https://citizan.org.uk/low-tide-trails/mersea-island-changing-minds-changing-coasts/ which is a superb reconstruction of Mersea’s changing coastline over the past century based on photographs and personal recollections of local people.

Why Mersea’s coastline is retreating

One of the main reasons why our coastline is retreating is its geology. Much of this is sandy material sitting on a bed of clay. The rain percolates through the sandy material down to the clay. But the clay rather than letting the water trickle through, simply absorbs it – and becomes slippery and unstable – causing the overlying sandy material in the cliff to collapse. So, the cliffs at Cudmore would periodically collapse even if the sea never reached them.

However, the 30cm sea level rise over the past century has meant that the point in the cliff base where the clay meets the overlying sandy material now gets wetted much more often – causing the cliff to slump more often.

However, a lot of coastal erosion happens because of wave attack – and this particularly affects the south and south-east coast of Mersea Island. What is called “hydraulic action” - the shear weight of water hitting a cliff can cause very substantial erosion, with a cubic metre of seawater weighing just over a tonne. The cliffs also get eroded by what is called “corrasion” - the waves picking up stones and even boulders and hurling them at the cliff. In some of the cliffs at Cudmore you can also see cracks and fissures – like mini caves. When waves hit these – they seal off the entrance trapping air inside which becomes compressed – and then explodes when the wave retreats which can break large chunks off the cliff.

What is important to understand about wave attack is that the bigger the waves – the more each of these types of erosion are likely to happen. The further waves come from – what is known as the wave ‘fetch’ - the bigger they are likely to be. If you look at an atlas – you can see that, although Mersea is in an estuary, if the waves come from the right direction they can travel from over 100 miles away.

On Mersea we also see erosion caused by tidal currents – particularly in the channels such as Besom Fleet, Mersea Fleet and Thorn Fleet.

So why is coastal erosion increasing?

Well one reason is that since 1900 sea level has risen across the UK by about 30cm due to slightly warmer sea temperatures, with warmer water taking up a slightly larger volume. But with an additional 10cm or so of ‘relative sea level rise’ (i.e. the gap between land and sea) locally due to “isostatic readjustment”. This means that waves are now reaching higher up the beach – and wetting the junction of the clay and overlying sandy material much more frequently – causing it to collapse.

Another reason is that before WW2 much of the shoreline mud around Mersea used to be covered in eel grass, whose roots bound it together and whose long fronds helped dissipate wave energy. However, a combination of agricultural chemicals, the use of a now banned type of anti-fouling paint on boats – and some winters such as 1962/63 when even the sea froze for several weeks, killed it off.

We have also seen an increase in storms and storm surges over the last few decades – and it is often these big events which do the most long term damage.

Climate change

The mid-range projections from the UK’s Climate Change Committee suggest that UK sea level is likely to rise by around 20-30cm in the next 25 years, in other words by a similar amount to that which it has risen in the past 100 years.

The latest research suggests that climate change and associated sea level rise is likely to mean that that the rate at which coastal erosion is happening is likely to be about 60% more than it was previously. This is partly due to an increase in the frequency of storms and storm surges. However, the geology of our part of the coast – where cliff collapse happens when the junction of the clay and overlying sandy material gets wetted – may mean that it affects Mersea even more.

In fact, a major academic study published in 2022 of which areas of the UK were most likely to be affected by rising sea levels – found Tendring and the Blackwater estuary to be one of the most vulnerable area.

Decisions about how to respond to coastal erosion are set out in a large document called the Shoreline Management Plan (SMP). This is agreed between local councils and the Environment Agency every 10-12 years, although in practice the Environment Agency (EA) has by far the greatest control. It is only the most determined of councillors who can disagree with the Environment Agency’s recommendations – not least because they control the overwhelming majority of funding for sea defence.

The SNP for Mersea Island which was agreed in 2010 sets out policies of either “hold the line” (i.e. maintain existing defences) or no active intervention in the short term – which is up to 2025. However, in the medium term (2026-2055) the policy changes to “managed realignment” for much of the coast to the east of West Mersea and for the Strood Channel. “Managed realignment” – normally means deliberately breaching existing sea walls, with homes and roads protected by sea defences further inland. We have yet to see what the Environment Agency’s plans for this mean in practice – but it is something that we will need to keep a very careful eye on.

Dr Martin Parsons is a West Mersea own councillor and former teacher and examiner for A level Geography

In a recent Courier we looked at how sea level rise is likely to affect Mersea and nearby mainland villages, with the next 25 years likely to see something similar to the 28-30cm rise we have seen over the last 100 years. One of the major consequences of that is a significant increase in the rate of coastal erosion.

The changing shape of Mersea Island

For centuries land has been lost to the sea either through sea level rise or erosion – and often a combination of the two. For example, if we go back to Anglo-Saxon times when the Lindisfarne monk Cedd established St Peter’s church in Bradwell, it is quite possible that the Blackwater estuary was confined to the deep channel that is only about a third of the width of the modern estuary. Subsequent sea level rise has created the ‘flooded estuary’ that we see today.

As such the shape and size of Mersea Island’s landmass has changed dramatically over the years. However, not all of that has been directly due to sea level rise. Even in the last 100 years there have been very significant changes in the size and shape of the island due to erosion – as well as to a certain extent the deposition of eroded material on other parts of the island.

The grey ‘mud’ that you can see when the tide goes out was originally land – and much of it until relatively recently. For example, the Cocum Hills, which are now about a mile off Cudmore were until WW2 actual hills of mud, and in the 1920s and 30s cattle grazed in the ‘Cattle Gut’ – now offshore from Cudmore. While a century ago Cobmarsh island was around twice its present size. If you want to know more – have a look at https://citizan.org.uk/low-tide-trails/mersea-island-changing-minds-changing-coasts/ which is a superb reconstruction of Mersea’s changing coastline over the past century based on photographs and personal recollections of local people.

Why Mersea’s coastline is retreating

One of the main reasons why our coastline is retreating is its geology. Much of this is sandy material sitting on a bed of clay. The rain percolates through the sandy material down to the clay. But the clay rather than letting the water trickle through, simply absorbs it – and becomes slippery and unstable – causing the overlying sandy material in the cliff to collapse. So, the cliffs at Cudmore would periodically collapse even if the sea never reached them.

However, the 30cm sea level rise over the past century has meant that the point in the cliff base where the clay meets the overlying sandy material now gets wetted much more often – causing the cliff to slump more often.

However, a lot of coastal erosion happens because of wave attack – and this particularly affects the south and south-east coast of Mersea Island. What is called “hydraulic action” - the shear weight of water hitting a cliff can cause very substantial erosion, with a cubic metre of seawater weighing just over a tonne. The cliffs also get eroded by what is called “corrasion” - the waves picking up stones and even boulders and hurling them at the cliff. In some of the cliffs at Cudmore you can also see cracks and fissures – like mini caves. When waves hit these – they seal off the entrance trapping air inside which becomes compressed – and then explodes when the wave retreats which can break large chunks off the cliff.

What is important to understand about wave attack is that the bigger the waves – the more each of these types of erosion are likely to happen. The further waves come from – what is known as the wave ‘fetch’ - the bigger they are likely to be. If you look at an atlas – you can see that, although Mersea is in an estuary, if the waves come from the right direction they can travel from over 100 miles away.

On Mersea we also see erosion caused by tidal currents – particularly in the channels such as Besom Fleet, Mersea Fleet and Thorn Fleet.

So why is coastal erosion increasing?

Well one reason is that since 1900 sea level has risen across the UK by about 30cm due to slightly warmer sea temperatures, with warmer water taking up a slightly larger volume. But with an additional 10cm or so of ‘relative sea level rise’ (i.e. the gap between land and sea) locally due to “isostatic readjustment”. This means that waves are now reaching higher up the beach – and wetting the junction of the clay and overlying sandy material much more frequently – causing it to collapse.

Another reason is that before WW2 much of the shoreline mud around Mersea used to be covered in eel grass, whose roots bound it together and whose long fronds helped dissipate wave energy. However, a combination of agricultural chemicals, the use of a now banned type of anti-fouling paint on boats – and some winters such as 1962/63 when even the sea froze for several weeks, killed it off.

We have also seen an increase in storms and storm surges over the last few decades – and it is often these big events which do the most long term damage.

Climate change

The mid-range projections from the UK’s Climate Change Committee suggest that UK sea level is likely to rise by around 20-30cm in the next 25 years, in other words by a similar amount to that which it has risen in the past 100 years.

The latest research suggests that climate change and associated sea level rise is likely to mean that that the rate at which coastal erosion is happening is likely to be about 60% more than it was previously. This is partly due to an increase in the frequency of storms and storm surges. However, the geology of our part of the coast – where cliff collapse happens when the junction of the clay and overlying sandy material gets wetted – may mean that it affects Mersea even more.

In fact, a major academic study published in 2022 of which areas of the UK were most likely to be affected by rising sea levels – found Tendring and the Blackwater estuary to be one of the most vulnerable area.

Decisions about how to respond to coastal erosion are set out in a large document called the Shoreline Management Plan (SMP). This is agreed between local councils and the Environment Agency every 10-12 years, although in practice the Environment Agency (EA) has by far the greatest control. It is only the most determined of councillors who can disagree with the Environment Agency’s recommendations – not least because they control the overwhelming majority of funding for sea defence.

The SNP for Mersea Island which was agreed in 2010 sets out policies of either “hold the line” (i.e. maintain existing defences) or no active intervention in the short term – which is up to 2025. However, in the medium term (2026-2055) the policy changes to “managed realignment” for much of the coast to the east of West Mersea and for the Strood Channel. “Managed realignment” – normally means deliberately breaching existing sea walls, with homes and roads protected by sea defences further inland. We have yet to see what the Environment Agency’s plans for this mean in practice – but it is something that we will need to keep a very careful eye on.

Dr Martin Parsons is a West Mersea own councillor and former teacher and examiner for A level Geography

Sea level rise on Mersea

Mersea Island Courier 23 February 2024

Sea level rise on Mersea

As the front page of a recent Courier told us, last year for the first time ever global temperatures stayed more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. One of the most important consequences of that for those of living on Mersea and the nearby villages is that sea levels are likely to rise at a faster rate than they have been. In fact, the mid-range estimates from the UK’s Climate Change Committee suggest that in the next 25 years our part of the UK is likely to see a rise in sea level of around 20-30cm.

Global warming

Some of that is a natural rise in sea level, but most of it is due to the global warming which has been happening since the industrial revolution began. This has led to an increase in sea level right round the UK of around 2mm a year since 1900.

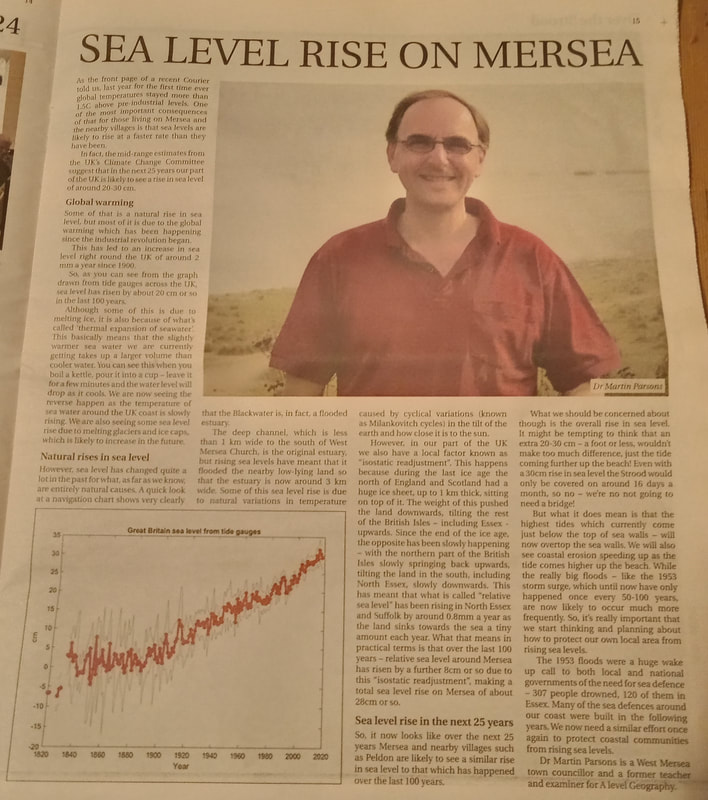

So, as you can see from the graph drawn from tide gauges across the UK, sea level has risen by about 20cm or so in the last 100 years.

Although some of this is due to melting ice, it is also because of what’s called ‘thermal expansion of seawater’. This basically means that the slightly warmer sea water we are currently getting takes up a larger volume than cooler water. You can see this when you boil a kettle, pour it into a cup – leave it for a few minutes and the water level will drop as it cools. We are now seeing the reverse happen as the temperature of sea water around the UK coast is slowly rising. We are also seeing some sea level rise due to melting glaciers and ice caps, which is likely to increase in the future.

Natural rises in sea level

However, sea level has changed quite a lot in the past for what, as far as we know, are entirely natural causes. A quick look at a navigation chart shows very clearly that the Blackwater, is in fact a flooded estuary. The deep channel, which is less than 1km wide to the south of West Mersea Church, is the original estuary, but rising sea levels have meant that it flooded the nearby low-lying land so that the estuary is now around 3km wide. Some of this sea level rise is due to natural variations in temperature caused by cyclical variations (known as Milankovitch cycles) in the tilt of the earth and how close it is to the sun.

However, in our part of the UK we also have a local factor known as “isostatic readjustment”. This happens because during the last ice age the north of England and Scotland had a huge ice sheet, up to 1 km thick, sitting on top of it. The weight of this pushed the land downwards, tilting the rest of the British Isles – including Essex - upwards. Since the end of the ice age, the opposite has been slowly happening – with the northern part of the British Isles slowly springing back upwards, tilting the land in the south, including North Essex, slowly downwards. This has meant that what is called “relative sea level” has been rising in North Essex and Suffolk by around 0.8mm a year as the land sinks towards the sea a tiny amount each year. What that means in practical terms is that over the last 100 years – relative sea level around Mersea has risen by a further 8cm or so due to this “isostatic readjustment”, making a total sea level rise of on Mersea of about 28cm or so.

Sea level rise in the next 25 years

So, it now looks like over the next 25 years Mersea and nearby villages such as Peldon are likely to see a similar rise in sea level to that which has happened over the last 100 years.

What we should be concerned about though is the overall rise in sea level. It might be tempting to think that an extra 20-30cm – a foot or less, wouldn’t make too much difference, just the tide coming further up the beach! Even with a 30cm rise in sea level the Strood would only be covered on around 16 days a month, so no – we’re no not going to need a bridge!

But what it does mean is that the highest tides which currently come just below the top of sea walls – will now overtop the sea walls. We will also see coastal erosion speeding up as the tide comes higher up the beach. While the really big floods – like the 1953 storm surge, which until now have only happened once every 50-100 years, are now likely to occur much more frequently. So, it’s really important that we start thinking and planning about how to protect our own local area from rising sea levels.

The 1953 floods were a huge wake up call to both local and national government of the need for sea defence – 307 people drowned, 120 them in Essex. Many of the sea defences around our coast were built in the following years. We now need a similar effort once again to protect coastal communities from rising sea levels.

Dr Martin Parsons is a West Mersea town councillor and a former teacher and examiner for A level

As the front page of a recent Courier told us, last year for the first time ever global temperatures stayed more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. One of the most important consequences of that for those of living on Mersea and the nearby villages is that sea levels are likely to rise at a faster rate than they have been. In fact, the mid-range estimates from the UK’s Climate Change Committee suggest that in the next 25 years our part of the UK is likely to see a rise in sea level of around 20-30cm.

Global warming

Some of that is a natural rise in sea level, but most of it is due to the global warming which has been happening since the industrial revolution began. This has led to an increase in sea level right round the UK of around 2mm a year since 1900.

So, as you can see from the graph drawn from tide gauges across the UK, sea level has risen by about 20cm or so in the last 100 years.

Although some of this is due to melting ice, it is also because of what’s called ‘thermal expansion of seawater’. This basically means that the slightly warmer sea water we are currently getting takes up a larger volume than cooler water. You can see this when you boil a kettle, pour it into a cup – leave it for a few minutes and the water level will drop as it cools. We are now seeing the reverse happen as the temperature of sea water around the UK coast is slowly rising. We are also seeing some sea level rise due to melting glaciers and ice caps, which is likely to increase in the future.

Natural rises in sea level

However, sea level has changed quite a lot in the past for what, as far as we know, are entirely natural causes. A quick look at a navigation chart shows very clearly that the Blackwater, is in fact a flooded estuary. The deep channel, which is less than 1km wide to the south of West Mersea Church, is the original estuary, but rising sea levels have meant that it flooded the nearby low-lying land so that the estuary is now around 3km wide. Some of this sea level rise is due to natural variations in temperature caused by cyclical variations (known as Milankovitch cycles) in the tilt of the earth and how close it is to the sun.

However, in our part of the UK we also have a local factor known as “isostatic readjustment”. This happens because during the last ice age the north of England and Scotland had a huge ice sheet, up to 1 km thick, sitting on top of it. The weight of this pushed the land downwards, tilting the rest of the British Isles – including Essex - upwards. Since the end of the ice age, the opposite has been slowly happening – with the northern part of the British Isles slowly springing back upwards, tilting the land in the south, including North Essex, slowly downwards. This has meant that what is called “relative sea level” has been rising in North Essex and Suffolk by around 0.8mm a year as the land sinks towards the sea a tiny amount each year. What that means in practical terms is that over the last 100 years – relative sea level around Mersea has risen by a further 8cm or so due to this “isostatic readjustment”, making a total sea level rise of on Mersea of about 28cm or so.

Sea level rise in the next 25 years

So, it now looks like over the next 25 years Mersea and nearby villages such as Peldon are likely to see a similar rise in sea level to that which has happened over the last 100 years.

What we should be concerned about though is the overall rise in sea level. It might be tempting to think that an extra 20-30cm – a foot or less, wouldn’t make too much difference, just the tide coming further up the beach! Even with a 30cm rise in sea level the Strood would only be covered on around 16 days a month, so no – we’re no not going to need a bridge!

But what it does mean is that the highest tides which currently come just below the top of sea walls – will now overtop the sea walls. We will also see coastal erosion speeding up as the tide comes higher up the beach. While the really big floods – like the 1953 storm surge, which until now have only happened once every 50-100 years, are now likely to occur much more frequently. So, it’s really important that we start thinking and planning about how to protect our own local area from rising sea levels.

The 1953 floods were a huge wake up call to both local and national government of the need for sea defence – 307 people drowned, 120 them in Essex. Many of the sea defences around our coast were built in the following years. We now need a similar effort once again to protect coastal communities from rising sea levels.

Dr Martin Parsons is a West Mersea town councillor and a former teacher and examiner for A level